Jakarta - The Origin (by Peter Fanning)

JAKARTA

Peter Fanning

On 22 June this year (2021) Jakarta celebrates its 494th birthday.

Settlement in the area certainly predated this, but this is the date accepted to be the date that Jakarta received its name (or at least the previous version of the name – Jayakarta). So the date is used for the birthday date, although not without some misgivings by many.

The mouths of rivers traditionally attract settlement because of access to the inland and fresh water, and a safer place for the ships of traders to anchor. And if trade is valuable, so much more significant is the settlement. So it is known that since the 1st century, traders from China, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, India and Arabia have anchored at the mouth of the Ciliwung River, to bring in silk, ivory, porcelain, cloth, tapestries, perfumes, pearls and incense, and to take away spices (cloves, nutmeg and mace) brought in by Javanese traders from (for many years) secret sources in the islands, preservatives, pepper produced locally, herbal medicines, gold, oils, woods, tamarind, rice and animal products. By the 16th century, Europeans began to arrive – Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French and English. The Portuguese were the first to arrive in 1513.

The mouth of the River Ciliwung – which flows from the mountains south of Jakarta - is the birthplace of the settlement that has become Jakarta, although it is not the only river in the area. It was actually also the mouth of the River Cideng. The Cideng appears to rise in the Duren Tiga area of South Jakarta, flows under Jl Thamrin just south of Bunderan HI (not to be confused with the West Flood Canal) and then along the back of Plaza Indonesia on its way to the sea. (And you thought that was just a big drain!). At its mouth it widens out and is known as Kali Besar. Kali Besar is often confused with the Ciliwung, although they had a common mouth until this was blocked off so that the historic Kali Besar would not totally silt up. The water of both was directed across to the River Krukut and so to the sea. The Krukut is a short river which flows out of the Cideng in Tambora, at the back of Glodok.

We obtain our early history of the area from stone inscriptions (prasasti) and the records arising from diplomatic and trade contacts with China and India. And pilgrims came from all over Asia especially to Borobodur. For 450 years during the late Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties, China was the greatest seafaring nation in the world. The high point was the voyages of Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 around the coasts of Asia and the northern coasts of Java and Sumatra, and west into the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, and south along the coast of Africa to Mombasa. His massive ships could carry up to 500 men, and made the ships of, say, Columbus look like tenders by comparison. The period culminated with the banning of the further construction of these ships in 1436, for reasons which are not clear. So they were off the scene by the time Europeans arrived.

Early Kingdoms

The first recorded kingdom in Western Java was that of Salakanagara, established when an Indian trader (Aki Tirem) married a local Sundanese princess in 200 AD. This was followed by the Tarumanagara Kingdom, founded in 358 AD, when another Indian on the run from a collapsed Indian kingdom married a princess of the Salakanagara Kingdom. This fellow is known to have been buried in the area of present-day Bekasi.

Tarumanagara extended to the Cipermali (now Brebes) River – the traditional border with Java to the east. The capital was called Sunda Pura (Holy Town). It is not clear where it was – it may have been at Tugu (North Jakarta) or Bekasi. And this was the first use of the name Sunda.

It appears that the Buddhist empire of Srivijaya (Sriwijaya) - centered on present-day Palembang – conquered Tarumanagara in around 650 AD. Srivijaya was a coastal trading empire controlling the northern coasts of Sumatra and Java, the Malay peninsula, and the southern coast of Thailand.

In 670 AD in a political deal to avoid a civil war, Tarumanagara was divided into the Sunda and Galuh Kingdoms, with the Citarum River forming the boundary. The Galuh Kingdom to the east extended across present-day Central Java.

Pajajaran

The King of Sunda at the time (Tarusbawa) established a new capital further away from the sea and upstream at a spot which centuries later became the city of Pakuan Pajajaran (or just Pajajaran). Pajajaran means ‘between two parallel things’, because the city was established between the Ciliwung and the Cisadane Rivers. The city of Pajajaran (and the Kingdom of Sunda) was destroyed by the (Muslim) Sultanate of Demak in 1579. The city on this site today we call Bogor. Already by this time, the Sundanese port at Sunda Kelapa had been claimed by Demak and renamed Jayakarta.

(Image: The port of Sunda Kelapa today)

At times however the two kingdoms (Sunda and Galuh) united under one king, and at other times they were allied though with different rulers. And over the years kings used different locations as their capital – shifting between Pajajaran and Kawali Ciamis (the capital of Galuh) and even Kuningan (near Cirebon). It was at Pajajaran when the Portuguese arrived in 1513.

The first European to sail from Europe to India (by way of the Cape of Good Hope of course) was the Portuquese explorer Vasco da Gama, in 1498 – a “pinnacle of world history”. The Portuguese arrived in Java 15 years later.

The last significant king of Sunda (Sri Baduga Maharaja) was known as Prabu (King) Siliwangi (a successor of Prabu Wangi, who had died as a result of a conspiracy hatched by the Majapahit prime minister, Gajah Mada, on behalf of his king, Haram Wuruk). Under the rule of Siliwangi, the Kingdom of Sunda had achieved great prosperity through efficient management of agriculture, and the thriving pepper trade. The year of his coronation in 1482 is celebrated as the birth date of Bogor, although urban settlement in this area pre-dated this as we have seen.

It is this prosperity which proved the undoing of the kingdom.

The king built a road to Sunda Kelapa (Sunda Kalapa) at the mouth of the Ciliwung River, which became his major port.

Sunda Kelapa was not originally the main port however – that was west along the coast at Banten, and appears to have been so since the 12th century. Pepper was grown nearby, and on the other side of the Sunda Strait, also part of the Sunda Kingdom. However, Banten was gradually silting up, and Sunda Kelapa had better access to Pajajaran anyway. It became the main port from the 13th century.

Following naval expeditions by the Ming Chinese Zheng He, who was also a Muslim, during the period 1405 to 1433, Muslim Chinese and Arab communities had been established in Semarang, Demak, Tuban (west of Surabaya) and Ampel. The vast Hindu/Buddhist Majapahit empire (with its capital in what is now Trowulan in East Java) was conquered by Muslim forces by 1527 – and principally in Java by the Sultanate of Demak, the nominal regional ruler. With the fall of Majapahit, the only Hindu Kingdoms left in Java were Blambangan in the far east, and Sunda in the west.

The port of Cirebon was lost by the Sunda Kingdom in 1482, and it became the Sultanate of Cirebon. Over time, the Sunda Kingdom became known as the Kingdom of Pajajaran, following the name of its capital.

Portuguese

Concerned at the growing influence of the Sultanate of Demak, Prabu Siliwangi sent his son to the commandant of the (Catholic) Portuguese fort at Malacca, Jorge de Albuquerque, to invite the Portuguese to sign a peace treaty, trade in pepper, and build a fort at Sunda Kelapa. In 1522 the Portuguese sent Captain Henrique Leme to sign the treaty which was done on 21 August 1522. On the spot where the fort was to be built near the mouth of the rivers, the parties placed a memorial stone.

This stone was rediscovered in 1918 when a house was being demolished at the corner of what is now Jl Cenkeh and Jl Nelayan Timur (on the east bank of Kali Besar, near the railway line), suggesting the coastline was then some 400m to the south of the Lookout Tower. The Lookout Tower is referred to simply because it is a significant landmark in the area. It was erected only in 1839, but on top of one of the bastions (Culemborg) of the post-1619 Batavia city wall, by then demolished, which bastion was in turn erected on the site of the Muslim Prince Jayawikarta’s guard post – about which see below. The stone is now in the National Museum (it used to be near the entrance, but I could not find it last time I looked).

(Image: The 1522 treaty stone)

Jayakarta

However the Portuguese were distracted by problems in India (Goa) and did not build the fort as agreed, and did not return until 1526, and were not able to prevent a Muslim takeover. A Muslim crusader, Fatahillah (born in Aceh, but recently returned from Islamic studies at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, and itching for a fight) was commissioned by the Sultan of Demak to conquer the Sundanese Kingdom ports of Banten and Sunda Kelapa for Islam, which he duly achieved on 22 June 1527, with 1,452 troops from Demak and Cirebon. His victory over the Hindu rulers at Sunda Kelapa was greeted by himself as a ‘Glorious Victory’, or Jayakarta. This is the date we celebrate as the birth date of Jakarta. Again it was not actually the beginning of urban settlement in the area.

The Portuguese were permitted to resume trading, but they were challenged by the Spanish and English, and, by the late 16th century, by the Dutch, who first arrived on the scene in 1596. In 1601 the Portuguese lost a naval battle to the Dutch in the Bay of Banten.

United East India Company

The (Dutch) United East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) was formed in 1602 to raise money for Holland’s fight to win independence from Spain, and at the same time to undermine the Spanish sources of wealth. It was established by royal charter, which gave it quasi-governmental powers – a common method of establishing foreign trading companies by colonial trading powers. It was not the first company to issue shares – that had been done in Roman times – nor the first in the ‘modern’ times (the British – originally English - East India Company had been established in 1600). But all its shareholders had limited liability (which was a first) and its capital was permanent – that is, could not simply be withdrawn by the investor (also a first). Therefore shares could not be liquidated, but could only be sold through the Amsterdam Stock Exchange which it established for this purpose (another first). It was the biggest of such companies. It was overseen by the Lords (or Gentlemen) Seventeen (Heeren XVII), appointed by the six Dutch Chambers which had raised its capital. And it was able to pay an annual dividend of 18% for most of its 200-year history (until nationalised on 1 March 1796 in financial ruin).

Dutch trading posts were established in Banten (1603) and Jayakarta (1611), but VOC headquarters were in Ambon, near the source of the spice (which source was no longer a Portuguese secret). However this location was too remote from other VOC activity in Japan and India – let alone Africa - so a location in the Straits of Malacca was sought.

Batavia

A subsequent Muslim leader in Jayakarta, Prince Jayawikarta, had his palace on the west bank of the Cideng/Kali Besar (about where the Hotel Omni Batavia now stands). It appears that the mouth of the rivers was then at about where the Lookout Tower stands. The Prince had a guard post erected there (where the Lookout Tower now is) to control the mouth of the river. The Dutch had first arrived in 1596, and in 1611 were allowed to build a warehouse and houses on the opposite (east) bank, where the Prince could keep an eye on them.

(Image: Kali Besar today)

Five years later he allowed the English to build their own little settlement on the west bank, and a fort close to his guard post. He was depending on the English presence to protect him from the belligerent Dutch.

In 1618 the English seized a Dutch ship at Banten, in retaliation for which the Dutch burned down the English settlement in Sunda Kelapa. Prince Jayawikarta in turn attacked the Dutch settlement across the river. The Dutch commander was arrested and the Prince entered into a formal friendship agreement with the English. However the Sultan in Banten did not agree with this development and sent soldiers to arrest the Prince and bring him to Banten. The VOC Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen headed off to Ambon to obtain reinforcements.

There are differing accounts of what happened next. One account has it that the English simply pulled out and the Sultan of Banten did nothing further. A small group of Dutch traders and sailors holed up in their fortified warehouses spent the early months of 1619 simply getting drunk, highlighted by deciding on 12 March 1619 to call their outpost Batavia (after a mythical 15th century Germanic tribe). When Coen returned on 30 May 1619 he took control of ‘Batavia’. One account has it that he “stormed Jayakarta”, but it appears the reality is that it was virtually abandoned and his for the taking.

So began a period of 330 years of Batavia under Dutch control, less 5 years under the the English from 1811 to 1816, and 3 years under Japanese control from 1942 to 1945. (The lasting influence of the British on Jakarta is that we drive on the left – most of the time!)

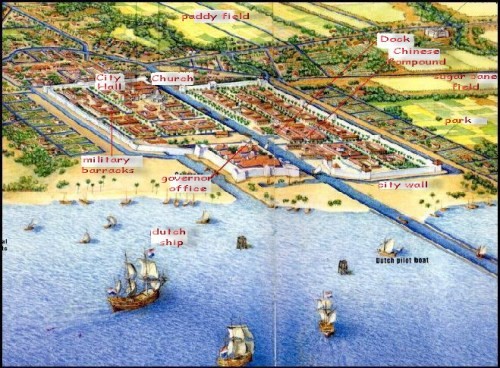

(Image: A representation of the walled city of Batavia (with the fort in the foreground). Kali Besar is represented by the dark blue waterway in the centre)

Jakarta

The story of Jakarta then (after 1619) becomes largely the story of the VOC (until its nationalisation on 1 March 1796 and dissolution on 31 December 1799), and subsequent Dutch government control, and the British interregnum under Thomas Stamford Raffles. These, and the stories of the Japanese occupation, and development since 1949, are stories for another time.